☠ The Dead Memorandum [#2]

The Subtle Art of Leaving Things Out

I am writing and publishing a novel titled Plath is Dead.

The Dead Memorandum [1] chronicles my imperfect progress.

This is a work of nonfiction.

The Dead Memorandum [#2]

The Subtle Art of Leaving Things Out

The press of bodies on a crowded cobblestone underpass. Flesh and fur, metal and feather, carapace and stone, music and muslin mingle past one another in the street. At my step, a pack of Scutlings scamper off into an ally, their antenna trailing behind like streamers in the wind. A Bifer spits a great red wad at my shoe, and I skip to miss it by a hair's breadth, patting his shoulder as I pass. He yawns a harumph (friendly old bog) , the red goop trailing from his jaw and into the cobblestone. I round the corner and the city opens to me like a flower: a great, sweating, stamping, gnawing, guffawing, flower.

The gooey center of the inhospitable UN-verse. The haven of Miscasts and Storyborn, anyone botched or abandoned by a Barren, anyone on the run from B.O.R.

I crane my neck, and up above, the city bends and turns. We are, all of us here, walking and skipping and puking and slapping inside of a great sphere with a floating gray sun at its center, a sun whose light is insufficient and unceasing.

Nastiest bog in the great Tapestry of Worlds, City of Wyrms: Endling.

Always good to come home.

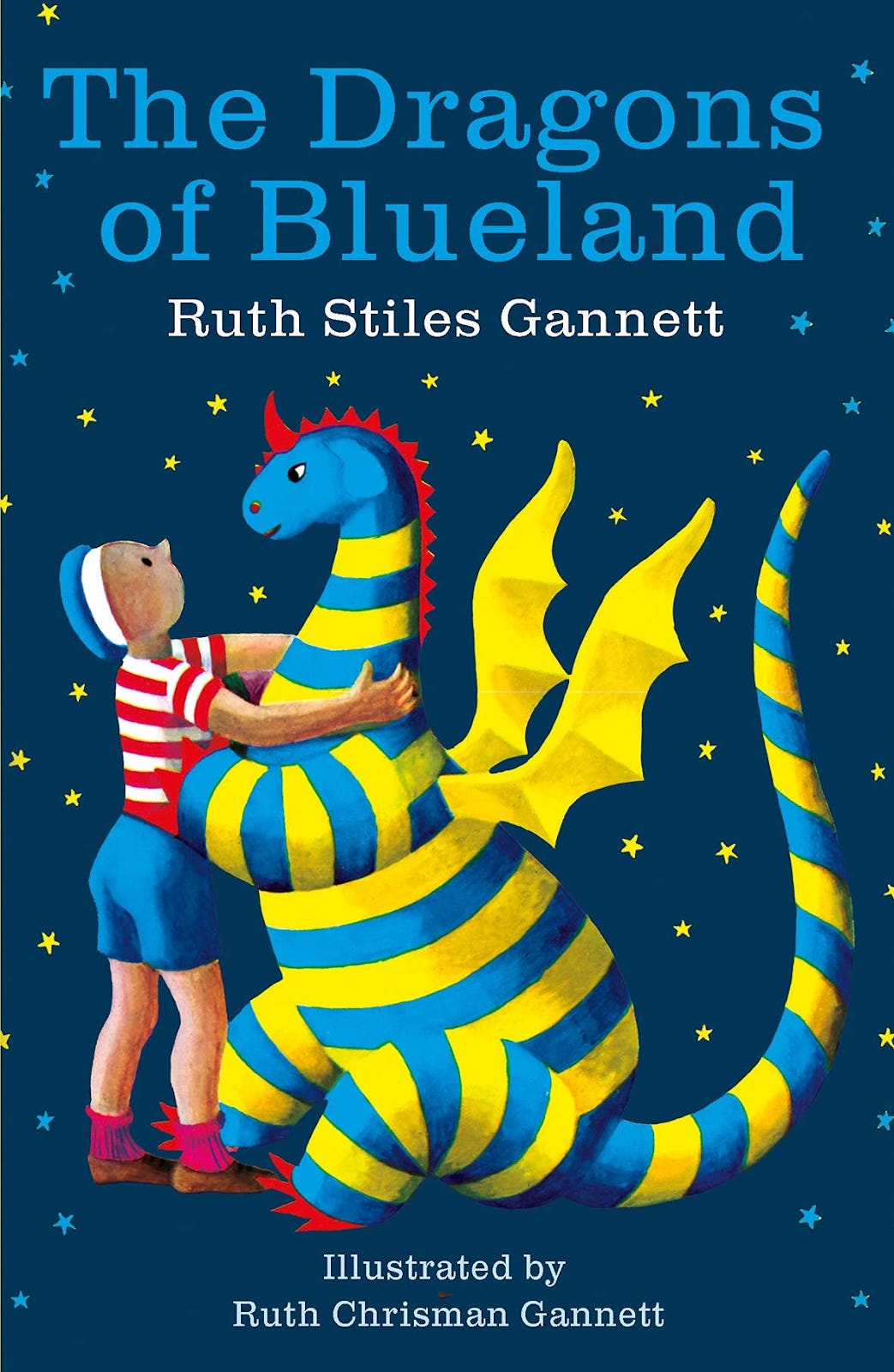

I was bit by the writing bug early in life. Like “ten years old” kind of early. I hit all the usual pit stops on the road to inspiration: Narnia, Middle Earth, The Trumpet of the Swan… but the series that made me want to write A Proper Book was The Dragons of Blueland.

True to my inherited puritan ethic, at the ripe old age of ten I had already “written” a story years prior. The story in question was a dozen page treatment called Jaybird the Puppy. I say “written” (in scare quotes) because I was five and therefore could not write per se. I dictated the story to my parents, babysitters, older siblings, pretty much anyone who would sit at a keyboard, listen, and type while I paced the hardwood floorboards and rambled visions of what the family dog got up to when no one was watching, like a strange, homeschooled, autistic-adjacent Don Draper.

Because we never actually knew Jaybird as a puppy, inheriting him in his middle years, I think my childhood imagination needed to fill in the gaps. My brain filled in a whole series similar in scope (if not content) to Animorphs or Goosebumps; there would be Jaybird the Puppy, then Jaybird the Teen and then a litany of action/adventure stories detailing Jaybird’s various heroic exploits journeying to places at the far corners of my imagination, places I had never been and likely never would go: Jaybird in Space, Jaybird in the Haunted Castle, Jaybird at the Pound… But I never wrote any of the other planned entries1 because I realized that my true audience was sitting on the floor right in front of me; I was fortunate to have two very kind and patient brothers who were more than happy to sit and listen to (or at least not interrupt) my stories while they fiddled with Legos and K-NEX. They heard it all (whether they remember is another question…): Jaybird the Puppy, The Big Bad Boys2, Shang and Chan Li3, Bruce Steel and Iron the Robo Dog4, and on and on…

Then came Blueland and my ambitions changed forever (if, perhaps, not for good). I would no longer story tell! I would story write!

The plot of The Dragons of Blueland is simple. According to Wikipedia:

“Boris the dragon contacts Elmer … to ask Elmer's help: several men have found his family of dragons and are proposing to sell them to zoos and circuses. Elmer runs away from home again and helps Boris's family to scare off the men permanently [emphasis mine].”

I think what hooked me was the story’s finality. In a surprisingly poignant, melancholy ending Elmer and Boris (yes… Boris is the dragon’s name...) part ways for good. Elmer goes back home to live a regular human life, to grow up and work a regular human job while Boris (yes… Boris) goes into hiding with his family. Before splitting, Elmer hugs… the dragon’s neck and they cry and say a tearful goodbye.

Forever.

If that isn’t enough to melt your nine year old heart, the whole image is depicted on the cover in resplendent blues and yellows and reds. Many of my memories are likely total bullshit, but I speak with utmost confidence when I say I remember exactly how sad this ending made me feel.

In retrospect, I have some suspicions about why it hit so hard. I grew up in a subgenre of the Christian tradition I can only describe as “incessantly optimistic,” the general vibe of which can be summarized by the lyrics of the ol’ timey hymn “When We All Get to Heaven” which, to my recollection, we sang in church about seventeen times a week: “When we aaaaaaaaaall get to heaven, what a day of rejoicing that will beeeeeeee, when we aaaaaaall see Jeeeeeeeeesus we’ll sing and shout the victoreeeeee. (VICTOREEEEEE!).”

There were no bittersweet endings in stories of my baptist youth. There were no ambiguous or tragic endings either. Everything began and ended in a happy rictus smile of creation and redemption with absolutely no room for enduring sadness, no room for tears; such things as “tears” and “sadness” were glitches in our glass-darkly-world, bugs that would be ironed out by God himself once the beta testing phase was over and we (not they, we) “aaaaaaaaaall” got to heaven.5

In this context of oppressive, internalized optimism, I found The Dragons of Blueland sort of scandalous. Encountering such a definitive and bittersweet ending in a story was my, perhaps, first deeply felt brush with death in all its finality. It infused me with a grand and terrible responsibility--I WOULD REVIVE THE SERIES! I WOULD WRITE A FOURTH BOOK! I WOULD BRING ELMER AND BORIS BACK TOGETHER FOR A PROPER, HAPPY ENDING WHERE BORIS’S FAMILY COULD LIVE WITH ELMER’S! THEY WOULD MOVE IN TOGETHER ON A RANCH WITH PLENTY OF SPACE AND PLAY IN BLISSFUL PARADISE FOREVER!

With time, the specifics of my ambition would (of course) fade, but I’ve never really forgotten what it felt like to learn that some stories remain untold on purpose, that to tell a story necessitates not telling millions of other possible stories.

To tell an effective tragedy, the writer must plant in the mind of the reader the idea that the characters could be happy if it weren’t for who they are as people. One has to imagine Macbeth confiding his ambition and jealousy in Duncan to feel a sense of gross catharsis at all the nighttime chest stabbing. So too with Frodo getting on that boat to go to The Grey Havens. It is only sad because we see Sam standing on the dock bawling his eyes out, wondering what it might be like for him and dear Mr. Frodo to live out their days together as… gardener and employer?6 To put it another way, some narrative truths about characters disallow other narrative truths (Frodo and Sam can’t part ways for good if they move in together, grow old, and die side-by-side. Tolkien couldn’t have it both ways so he picked the bittersweet option).

Once I realized this truth about stories the whole “art via absence” thing crystallized, for me, into full blown creative paralysis. I’ve since figured big parts of it out, but it recrystallizes on the bad days. Because a dozen or more untold and untellable stories exist in my brain at the same time I feel pain, frustration, angst, curiosity, inaction, and despair.

In addition, the idea that to tell one story entails not telling dozens of others has haunted me since The Dragons of Blueland7 specifically in that I struggle leaning into cathartic sadness. I don’t like to see people (even imaginary people) suffer. It says a great deal about my neurosis and people pleasing tendencies that I often refuse to allow genuine sadness at the end of a story even if that is what the story is screaming for. I’m working on that. Identifying the problem is the first step. I’m not sure what the second step might be.

My current strategy is to try and tell a story where “the road less traveled” and all its lost opportunities and regret and sadness are intrinsic to the narrative. Plath is Dead (whatever it may eventually turn into) is a story about lost things that cannot be recovered. It is about humor in dark places. It is a sad story, or at least a story with fiendishly sad parts intricately involved in its construction. Most of the characters are “low level,” inconsequential little people who deal with the powerlessness that comes from being left out of something important: an intern who works for The Bureau of Rationality, a literal Office Drone who sees with omniscient fly eyes all the worlds in a magical multiverse but cannot leave its’ desk because it’s hard wired into an archaic computer, an old smuggler “not named” Prufrock who can’t seem to locate some very important memories, like his name, or his daughters identity, a little girl growing up in a house made of books with no one around to talk to, an assassin who calls herself Shadow and Jack the Ripire, the mutilated man thing that tails her at every turn.

These characters exist a certain way even though they could just as easily exist differently, merge into one, or split into a dozen.8 I suppose writing a story is deciding to make certain people real, to give them hearts and minds and dreams with an overwhelming desire to hide the reality of their hearts and minds and dreams.

In that way, the story people become like you and me.

Apparently, in The Europeans the novelist Henry James writes of one character “...there was what she said, and there was what she meant, and there was something between the two that was neither.” I’ll shamelessly plagiarize his words to make my point. When writing a story, there is something that the characters are, and something that they aren’t, and something between the two, that makes the story work.

I’m trying to write characters who exist in the middle space between what they are and what they could be.

Here’s to hoping!

Prophetically, the irresponsible behavior of starting a creative project only to give up after the first rush of excitement has stalked my subsequent years.

I once tried to make a podcast…

I once tried to launch a kickstarter for a board game…

I once tried to write a manual for a roleplaying game…

I once drafted a novel only to shelve it and start another draft, and then shelve that etc. etc.

For every work I complete, I have buried five caskets in my crawlspace packed to the boards with forgotten drafts.

A gang of fictional “toughs” featuring my brothers and their friends.

Kung Fu fighting superhero brothers from an ambiguous Asian country that was basically a white suburban home schooled eight year-old’s idea of what mythical China was supposed to be (complete with Katanas and Nunchucks!) This world was heavily inspired by Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles, Daredevil Comics, and any cartoon featuring an “Asian” character between 1995ish-2005ish.

Imagine blending Inspector Gadget silliness, RoboCop ultra violence, and post 9/11 anti-terror sensibilities. “Oh gee oh my! Iron! We have to stop the terrorists from Jihading the Ameri-mall but we don’t know where their treason bombs are hidden! Go-Go Gadget Waterboard!”

This is a slight exaggeration, but it certainly illustrates well the truth that some childhood dreams deserve to stay firmly planted in the ignorance of childhood lest they grow into ugly, wart covered adult nightmares.

A similar form of existential optimism is defended quite eloquently by G.K. Chesterton in his essay “On Running After One’s Hat” and defended less eloquently by C.S. Lewis in his novels The Last Battle and The Great Divorce, each of which portrays a kind of heaven that is all-encompassing, infinite, and incessantly blissful.

Kidding! Possible clandestine lovers, definite close friends, and gardener → employer.

I don’t think this interest is remotely unique. Within the genre of speculative fiction there are serious treatments like the one Margaret Atwood supplied with “Happy Endings” or the recent film Everything Everywhere All at Once. There are also glutenous, bloated, frivolous, unnecessary, and exhausting tirades like Marvel’s What if…? or any piece of media involving a multiverse (sigh).

Ultimately, I think lazy multiverse stories directly misuse the technique. They try to employ it so that all things can be true at all times for all fans and no one has to feel sad because the story is operating like some kind of clunky algorithmic VR where the viewer gets gently patted on the head-canon and told that their favorite pet theories “are true, we promise! Now please continue playing the slot machine that is our story so that we don’t lose these jobs we just landed.”

George Lucas said in an interview that Obi-Wan Kenobi was originally the only Jedi in Star Wars Episode 1: The Phantom Menace, but his role was eventually split to add Qui-Gon Jinn to the mix. There are, I am sure, more venerable and interesting examples of characters splitting or merging. Unfortunately, my brain has a knack for only remembering cringe-inducing details and forgetting everything else.

Hard to get the image of a “happy rictus smile” out of my head!